by Sean Chaffin

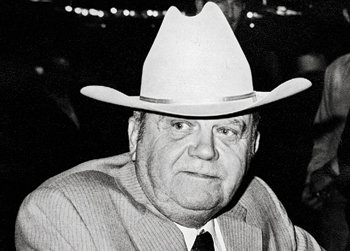

• Legendary poker player Doyle Brunson played and partied on Jacksboro Highway.

• See the online exclusive interview HERE.

The scene is a dark room in the 1950s off Jacksboro Highway, a six- to seven-mile road running from downtown Fort Worth to Lake Worth featuring a mélange of saloons, back-room gambling halls and any type of vice your brain might be able to imagine. Smoke billows in the air and poker legend Doyle Brunson is at the poker table mixing in bets and bluffs. The action is big and "No Limit Ace-to-Five" is the chosen game for the night.

At the table for five days straight, Brunson has only gotten up from his spot for a bite to eat and visits to the men's room. Big money was at hand and, apparently, the money was too good to leave. Constantly nursing a cup of coffee and a cigarette to stay awake, Brunson found himself locked in battle in what he would later describe as the "longest poker session of my life." A man named Virgil had also been seated at the table, taking pills, drinking and smoking to stay awake.

An employee of a slaughterhouse, Virgil came out ahead of Brunson in a key hand, Brunson writes in his book The Godfather of Poker. Brunson, who would go on to win 10 World Series of Poker championship bracelets (the biggest trophy in professional poker) and be inducted into the Poker Hall of Fame, acknowledged his opponent's win. Virgil then grabbed his bottle of whiskey, tilted it back and gulped down a shot. It would be his last. While reaching to scoop in his pot, the man dropped dead on the table.

"That's when I found out how cold-blooded poker players can be," Brunson writes. "All of us had known Virgil and played with him many times. After the paramedics took him away, the game resumed and we played another 24 hours."

Brunson's tale is one of many of the famed strip of roadway. In the 1950s, if you were interested in gambling, drinking, cutting loose on a dance floor, and just raising some hell in general, Jacksboro Highway was the place to be.

A Wild West Town

A good roll of the dice or deal of the cards could always be found in Fort Worth in the late 19th century. Hell's Half Acre, as the city's red light district was known, encompassed several blocks around today's Tarrant County Convention Center. Booze, prostitution and gambling were mainstays –and lawmen chose to look the other way rather than upset a key economic engine for the city. Cowpokes who drove their cattle through the city knew that a stopover for a night could include dancing women (and a woman for the night at the right price), drinks and some gambling, followed by a much-needed bath after hitting the trail. Fisticuffs and murder were also common in the Half Acre, where gun-toting cowboys and heavy drinking often created a combustible combination.

"Fort Worth was a wide-open town in the 1870s. It was lively. Rowdiness and respectability lived side by side. Plenty of people were both, rough, tough and respectable," read a 1949 article about the area in the Fort Worth Press. "A knifing was as ordinary as a parking ticket today."

And eventually the good times would come to an end, thanks to stricter police enforcement and religious campaigns warning against the vice occurring in the Half Acre in the years preceding World War I. But the gambling, booze, prostitution and wild times would find a new home in the 1940s and 1950s –Jacksboro Highway, Fort Worth's version of Bourbon Street that would definitely live up to the legacy left by Hell's Half Acre.

From military men to plant workers to degenerate gamblers, Jacksboro Highway's few miles of roadway (officially known as Texas Highway 199) stretching away from Fort Worth toward Azle, Jacksboro, Wichita Falls and Amarillo attracted a unique cast of characters out for a good time. With gambling officially illegal in Texas, Thunder Road, as the stretch of highway became known, was one of the few places in the state one could plunk down a few dollars on black or red at the roulette wheel or roll the bones at the dice table. The state may have banned gambling, but a little bit of Fort Worth's Wild West mentality continued.

The Clubs, Gambling and Poker

A lifelong poker player and son of a club owner, Richard Davis, grew up in this atmosphere. The 76-year-old grew up in Fort Worth and now lives in Haltom City. His mother, Inez Mortenson, ran the famous Inez 50/50 Club, a small club at the intersection of Jacksboro Highway and Roberts Cut Off Road. Mortenson, who passed away a few years ago at 87, was as interesting a character as the patrons who frequented her club –allegedly named for the odds of someone leaving in one piece after a night out on the neon-soaked highway (although she said it had to do with how she treated customers: 50 percent of giving them full drinks and honest change and 50 percent making them feel welcome.

Mortenson was married 11 times, her first marriage at 15. Davis says his mother married a man at age 21 who was deeply involved in the club business in the area. She began picking up the business from her husband, and the 50/50 became popular for "drinking, dancing and good fellowship," as her son puts it. Through the years, Mortenson brought home many crazy tales of life on Thunder Road. She said Willie Nelson frequently performed at some of the clubs that she ran through the years. While she may have been petite, Davis says that his mother had no problem getting aggressive with an unruly customer.

"She was just trying to make a living," Davis says of her career as a club operator. "She was 4-foot, 11-inches and 150 pounds but not afraid of the devil himself. My mother put in a lot of hours on the Jacksboro Highway."

As the son of a club owner, Davis had access to many of the clubs along the highway. One of those that always intrigued him was the Chateau Club, an upscale club with a long drive and private gate at the entrance. More like a classy Vegas casino than a back-room gambling joint, Davis says it was popular with Fort Worth's upper crust, with private rooms for gambling and a steakhouse known for its excellent cuisine.

"It was where all the local celebrities would gather for a night out," he says. "It was first class."

An average night might feature a Cowtown power couple dressed to the nines out for some cocktails, fine dining, dancing and, of course, gambling. Beyond the security measures of a private gate, the Chateau reportedly had a tunnel for patrons to make their exits in case of a raid by law enforcement. Gambling equipment could also quickly be hidden in compartments in the walls. It was that type of thoroughness that helped many underground gambling joints survive the occasional law enforcement raid –that and payoffs to easily swayed squad officers, according to Ann Arnold, author of Gamblers and Gangsters, which uncovers the dramatic history of Jacksboro Highway.

Catering to customers of a more elite social status, the Skyliner Ballroom was a favorite for many. The place is remembered as one of the wildest clubs in the area and opened in the 1930s as the largest dance hall in the city. With a white stucco façade, the building featured a dance floor of 2,500 square feet surrounded by blue carpet. Fine wine was served to patrons seated on rose-colored couches and chairs. A visual highlight was the mural of the Fort Worth skyline near the entrance as was a 14-piece orchestra that played as Fort Worthians danced the night away. Louis Armstrong was among the celebrities who played at the fabled club.

While the Chateau may have attracted some of Fort Worth's finest, numerous clubs catered to everyone from military members on leave to Fort Worth residents who had an itch to gamble and were simply looking for a night out. The Rocket Club proved a popular North Fort Worth club to drink beer and listen to rock n" roll. The club's sign remains a lasting reminder of the highway's heyday and still stands at the location at 2130 Jacksboro Highway, now a muffler and welding shop. The exterior of the white building now offers up notes on service specials rather than beer specials, but the sign sitting atop the entrance features the words "Rocket" surrounded by an outline of a flying disc with a star on the right edge. The sign now faces a used car lot across the street. Decades ago, the futuristic red and blue neon beckoned revelers from across the Metroplex. Other popular clubs included the Magic Lounge, Massey's, the Black Sands and numerous others.

Many would argue that the best gambling action was at the 2222 (Four Deuces) or 3939 clubs. Other establishments along the highway may have offered gambling and poker, but these two clubs were the center of the Jacksboro Highway gambling scene offering everything from horse wagering to craps.

The Four Deuces was the idea of W.C. "Pappy" Kirkwood. Built in 1932 on a hill at 2222 Jacksboro Highway (hence the club's name), the Spanish-style home featured top-notch steaks, booze and free cigars for those gambling at the tables. On a given night, several hundred thousand dollars might change hands at the blackjack, craps, roulette and poker tables. Regular folks were welcome as were big names ranging from actor Gene Autry to House Speaker Sam Rayburn, who didn't gamble but joined Pappy once a year at the Four Deuces for drinks.

"Everybody in this part of the world knew the Four Deuces was a gambling joint. Including the cops," Pappy's son Pat Kirkwood told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram in 1991.

One can imagine there were numerous stories of wins, losses, and everything in between. One night in the Four Deuces" heyday, Pat Kirkwood told the newspaper that a high roller came to the joint in a brand new 1946 Cadillac and hit it big at the craps tables. The mysterious gambler left with Pappy owing him a cool $100,000, which he promised to pay the following day. When the player arrived the next morning, he sauntered to the dice table and offered a heads-up battle. Pappy accepted, and things did not quite go as the gambler expected.

"Pop won back all his money, all the cash the guy had in his pocket and all the credits he'd given him," Pat Kirkwood told the newspaper. "I drove the guy down to his hotel and dropped him off, then drove his new Caddy back to the club. Pop won that too."

For poker players, the Jacksboro Highway no doubt was an occasional stop on the Southern circuit –the name given to cities traveled by Texas poker players looking for a poker game with a good game, high stakes and hopefully several suckers at the table. Along with Brunson, legendary players (and Texans) included "Amarillo Slim" Preston (World Series of Poker champion, Poker Hall of Fame), Bob Hooks (WSOP runner-up), Bill Smith (WSOP champion, Poker Hall of Fame) and Bryan "Sailor" Roberts (WSOP champion, Poker Hall of Fame).

As these men were traveling from game to game, Jacksboro Highway would be an occasional stop for many including those looking for the latest game to hit the scene –Texas Hold "Em. Author James McManus notes that Texas was obviously the birthplace of the poker game that has become the most popular form in America. An expert on the history of the game and author of Cowboys Full: The Story of Poker, McManus notes that Texas Hold "Em grew out of the back rooms in Texas.

"Poker began in New Orleans around 1805 and aboard the riverboats moving up and down the Mississippi from that new American port," McManus said in an interview. "The history of Texas Hold "Em naturally begins in Texas about a hundred years later."

And for poker rounders (the name given players who traveled "around" looking for a game) like Brunson in the 1950s, Jacksboro Highway always proved to be ready for a game –Texas Hold "Em included. For years, Richard Davis set up poker games in the area and recalls playing many of the "old timers" as they made their way to north Fort Worth. Jacksboro Highway may not have been the hotbed of poker that the rest of the city was, but if there was a high-stakes game on any given day, rounders like Brunson would be there – all looking to leave with a pocket full of cash.

Murders and Mobsters

With its underground casinos, houses of ill repute, dancing girls, and clubs with bootleg liquor, Jacksboro Highway naturally attracted the type of "businessmen" who were more than happy to skirt the law, skim cash off the top and deal with their competitors by any means necessary.

It would take much more space than is allotted here to detail all the characters that made Thunder Road their stomping grounds, but a few names stand out. Tiffin Hall moved to the city from Missouri in 1920 and owned several establishments throughout Fort Worth, including many on Jacksboro Highway. Quiet and impeccably dressed, Hall owned the Mexican Inn, which served tacos and enchiladas on the first floor –and gambling on the second. Throughout his lifetime, Hall had his hands in numerous gambling operations throughout the Metroplex, notes Gary Sleeper, author of I'll Do My Own Damn Killin": Benny Binion, Herbert Noble, and the Texas Gambling War. Binion ran underground casinos throughout the Metroplex (and reportedly owned a piece of some Thunder Road establishments) before heading to Las Vegas to found the Horseshoe Casino and later the World Series of Poker.

"Hall never denied his gambling background but never admitted to being a big-time gambling operator," Sleeper writes. "Between 1922 and 1955, he was arrested 16 times, eight of those for gambling. But it was not until 1951 that Hall was identified as a major Fort Worth gambler –some said the kingpin –and an associate of Benny Binion. Even then, Hall would deny any connection with Binion or other Dallas gamblers."

A rodeo performer as a young man, George Wilderspin was another "businessman" who found his way to Thunder Road. He sold cattle to Binion. He later ran gambling at the East Side Club in Haltom City and had his hand in other clubs before running afoul of the law. He later got out of the business and continued to raise and sell cattle.

Leroy "Tincy" Eggleston and Nelson Harris were also major operators on the highway. Harris started his life in crime as a deliveryman for the Green Dragon narcotics syndicate and became a bouncer for some joints on Jacksboro Highway after serving two years in federal prison. He also ran a prostitution racket and a club out of his own house, according to Sleeper. Considered "one of Fort Worth's toughest and most versatile criminals," Eggleston ran joints on Thunder Road, and throughout his lifetime was charged, indicted or convicted for murder, gambling, assault, hijacking, robbery and burglary.

From 1940-1960, author Ann Arnold notes that 16 gangland-style murders went unsolved. One of the most noted murders would eventually lead to the wide-open gambling, bootlegging and general hell-raising that made Jacksboro Highway notorious.

The End of the Road

Up until Nov. 22, 1950, most people in Fort Worth paid little attention to the dancing, the liquor, the gambling, the prostitution, or even the mob that flourished on Jacksboro Highway. Then, Nelson Harris and his family were blown up while sitting in the family car. Photos from the time show a grisly scene as a crowd gathers around. The doors are blown off, and the blood-covered canopy of the convertible is blown over the rear of the car.

"The explosion, audible for blocks in all directions, roared inside the two-door 1950 coach parked beside the Harris" duplex apartment at 3105 Wingate as the couple started for a drive at 9:15 a.m.

Amazingly, no one ever stood trial for the murder, but that gang-style murder kick-started law enforcement officials to do something about the mob that ran gambling operations not only on the Jacksboro Highway, but also throughout Fort Worth. On March 31, 1951, a Tarrant County grand jury released the names of numerous people indicted for gambling violations, including Tiffin Hall, George Wilderspin and Pappy Kirkwood. Some would serve jail time, others would not, but the gambling would come to a stop in the ensuing years. Befitting Thunder Road's reputation, Tincy Eggleston was left off the list but met his own untimely death. Police believe Eggleston attempted an extortion plot for $5,000 and was scheduled to pick up his money on Aug. 25, 1955. The tables turned on the lifelong criminal. His body was later discovered by police in an abandoned well behind an unoccupied home outside the city limits. A bullet hole was found in the back of his head.

The indictments and news of the violence related to the "businessmen" of the Jacksboro Highway definitely had a negative effect. Gambling dried up in the next decade. Many may have known those who were running the gambling scene but, like the police, had previously looked the other way. Even poker legend Doyle Brunson accepted who ran the card games and played in them (on what he called Bloodthirsty Highway) but eventually chose to gamble in other parts of the state.

"I knew the kind of people they were and what they were capable of doing, but as long as you kept on the straight and narrow with them, you'd be accepted. And you'd stay out of trouble," he says of playing poker in the highway joints in the 1950s in The Godfather of Poker. "The money they won or stole, or whatever they did to get it, they brought to the poker games. I was there to win that money, and they were there to win mine. That's poker. We were much better players than our crooked cohorts, and we regularly relieved them of their ill-gotten gains. Then they'd go steal more money, come scurrying back, and we'd break them again."